From http://www.fwjackson.co.uk/

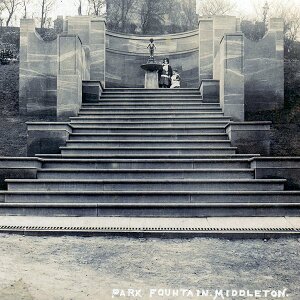

Frederick William Jackson was born in 1859 at Middleton Junction. He was one of three children, and his father worked as a photographer in Oldham. His two brothers were Vincent Jackson, a musician trained at Leipzig Conservatoire, and Charles Arthur Jackson, who was an art dealer and owned a gallery at 7 Police Street, Manchester. Charles gave considerable support to Frederick during his career, helping with both money and materials. Many of Jackson’s pictures bear labels inscribed with the address of his brother’s gallery.

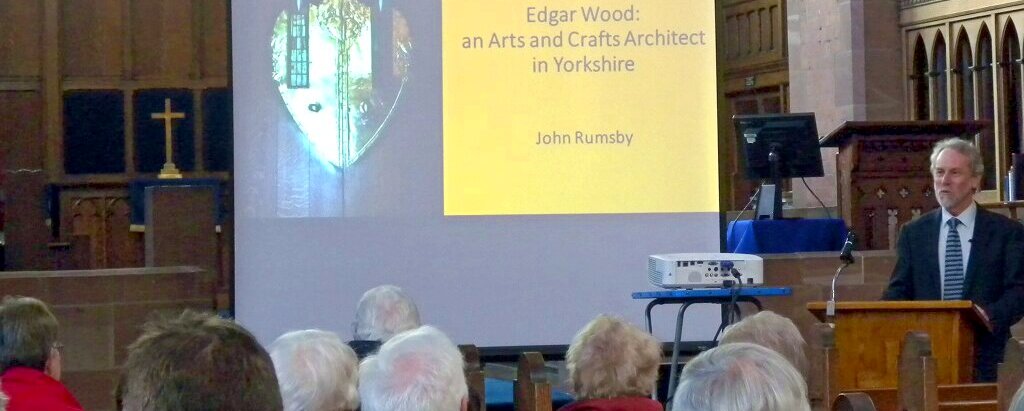

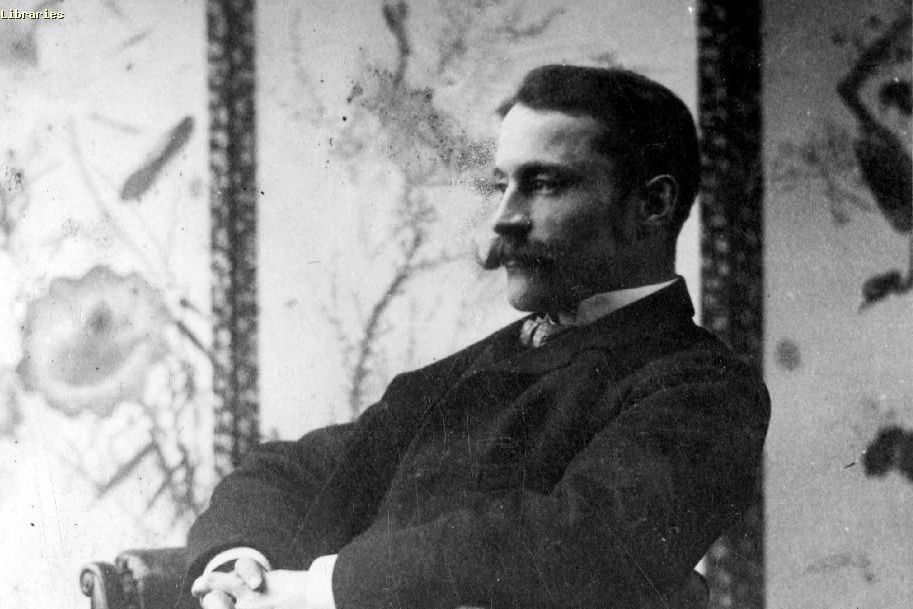

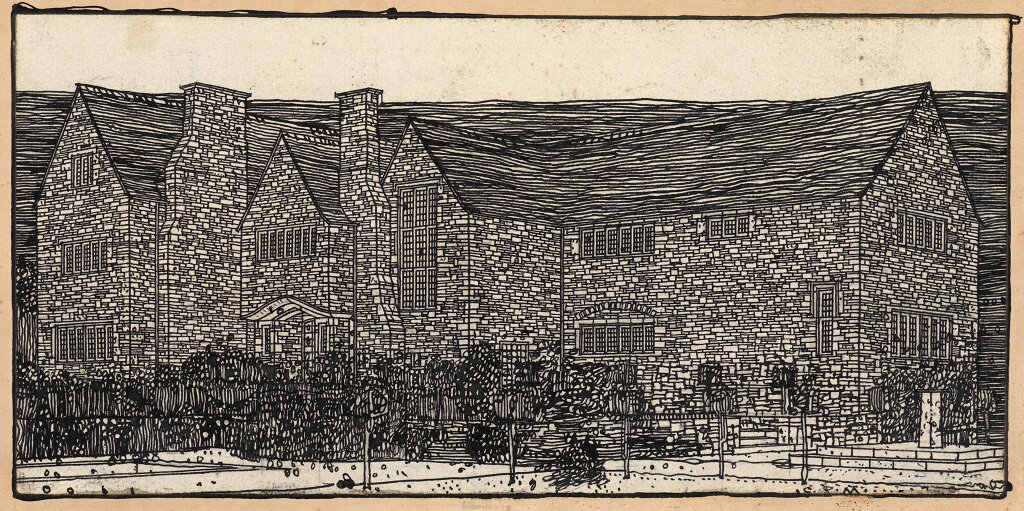

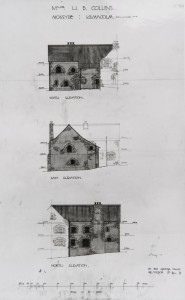

Jackson had relatively little formal training. His interest in painting was evident from an early age: as a boy, he went on sketching tours with his friend, the future architect, Edgar Wood. After leaving school, he attended evening classes at Oldham School of Art, where he studied painting under John Houghton Hague. (William Stott of Oldham was another of Hague’s pupils).

John Houghton Hague’s brother, Joshua Anderson Hague, was the leader of a group of young artists known as the ‘Manchester School’. Nearly all these artists had been trained at Manchester Academy of Fine Art and they met together in Wales at the studio of the self- taught, Joseph Knight, in the early 1870’s. They were influenced by the Barbizon School of painters and by Israels, Mauve and Maris, and they made a number of trips to Brittany between 1871 and 1878. The group was making, a considerable impact in the mid 1870’s and Jackson was drawn towards them, being influenced by their choice of subject matter and style of tonal painting. Academy where he attended life classes for six months. In 1880, he went to live in North Wales, where the artists H. Clarence Whaite, Joshua Anderson Hague and Edward Norbury were planning to found the Royal Cambrian Academy. He joined the already considerable number of Manchester artists living in the Conway Valley.

The 1880’s was an important decade for Jackson. He was made a member of the Arts Club in 1879 and a member of the Limners Club in 1880-1. Following the Manchester Academy exhibitions of 1880 and 1881, he was elected a member of the Manchester Academy of Fine Art. Over the next few years, he exhibited a good deal of his work, including two coast scenes at the Paris Salon in 1884 and “two splendid landscapes” there in 1885. In 1886, he became a founder member of the New English Art Club. He did not join its ten more progressive members (including Sickert and Steer) who worked in an Impressionistic as opposed to Barbizon inspired manner, and he did not exhibit at their separate exhibition of 1898 entitled ‘The London Impressionists’. In 1894, Jackson became a member of the Royal Society of British Artists. Throughout the ’90’s, and probably through his friendship with Edgar Wood, he became involved in the Arts and Crafts Movement. It was at this point that he did a number of mural paintings. His affinity with the Movement is evident in other areas of his work – his wash drawings to illustrate works by local dialect writers, Ben Brierley and Samual Laycock for example and his oil paintings of hand spinning and handloom weaving.

Returning from Wales, he went to Paris where he studied under Lefebvre and Boulanger. He remained in France for four or five years. It is most unlikely that he was influenced by those masters who taught him in Paris – they worked in a meticulous and academic style favoured by conservative French art lovers of the day, and totally alien to his own approach. At this time, Rochdale born Edward Stott was also in Paris, Studying under Carolus Duran, and Oldham-born William Stott and Henry Herbert La Thangue were studying under J. L. Gerome. During this period, the work of the Barbizon school painters was being hung in the Salon and Impressionism was at its height – with the stir it had caused still very much in evidence! (The first Impressionist Exhibition had been held in 1874 and the last was to be held in 1886).

After completing his studies in Paris, Jackson visited several European countries, spending most of his time in Italy, in Capri, Venice, Florence and Rome. He also visited Morocco before returning to England. He settled at Ivy Cottage, Hinderwell near Whitby, marrying Carrie Hodgeson, the daughter of a Yorkshire farmer. From there he exhibited frequently at the Manchester Academy and at the annual exhibition of the Yorkshire Union of Artists, as well as in London.

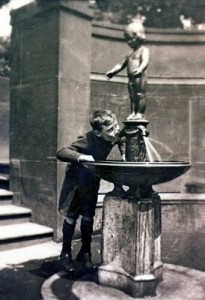

After 1900, Jackson travelled to Russia, France and Italy and, as some of his contemporaries noted, his late landscapes executed in these included some of his finest work. Jackson was liked and respected in his day and praised as an artist. It was generally felt that he could have achieved the distinction of R.A. had it not been for his reticence and modesty. He died in 1918 aged 59 and was buried in his native Middleton.