Yesterday, 17th December, I travelled up to Glasgow to see the Mackintosh Architecture exhibition at the Hunterian Art Gallery, before it closes on 4th January 2015.

The exhibition is the result of a research project into Mackintosh’s buildings and the practice that he worked for, Honeyman and Keppie, later Honeyman, Keppie and Mackintosh. Elsewhere at the Hunterian, you can visit the internal recreation of Mackintosh’s house and see his travel sketches and paintings.

There are no new major discoveries. Instead, the exhibition tries to rebalance the myths – the doomed romantic, Scottish nationalist, pioneer modernist etc. – simply by showing his drawings and the networks of professionals and patrons in which he worked. Through this everyday evidence you see another Mackintosh emerging, a team player and an exemplary professional working for one of Glasgow’s major architectural practices.

All of the famous drawings are exhibited and what immediately surprises is how large they are, much bigger than the prints in books. You can see his immaculate draughtsmanship, by which he stood out from his contemporaries. The work of Honeyman and Keppie is also shown. They were fine architects working in the styles of the day rather than Mackintosh’s Art Nouveau. There was quite a lot of collaboration between all three designers and Mackintosh could work just as well in the traditional styles, if he needed to.

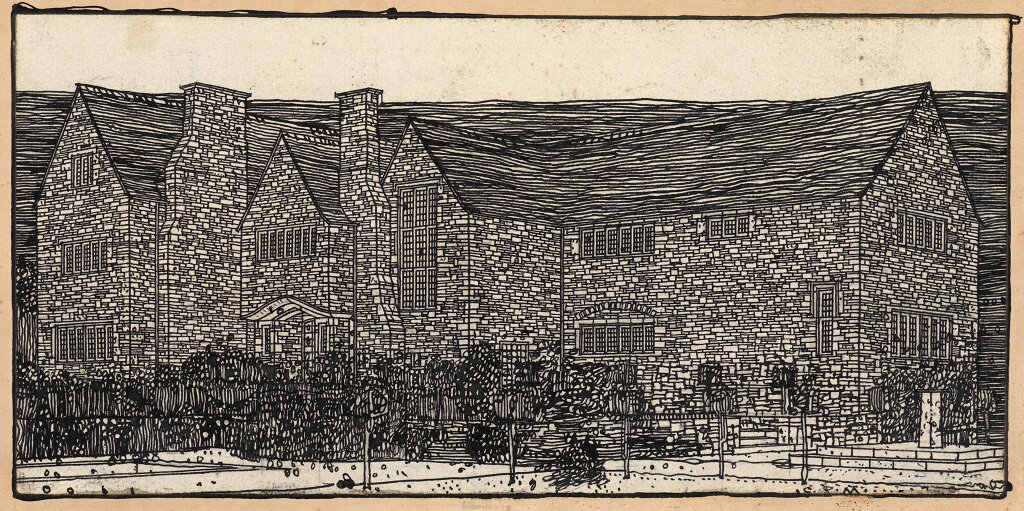

Mackintosh’s four large houses are highlighted. In these, his architectural progression is the reverse of other progressive designers, running from the almost abstract Windyhill to the highly expressive Hill House, to the Jacobean Auchinibert (featured drawing above) and finally to the vernacular Mossyde. You can see him absorbing ideas from the English Arts & Crafts movement, initially at Auchinibert, partly through the preference of the client. Mackintosh’s final house, Mossyde, shows him fully resolved as a vernacular Arts & Crafts designer – an astonishing change from Hill House of only a few years earlier. Mackintosh was an architect who could develop and embrace new ideas. It is a shame that architectural work dried up after 1910 then stopping completely in the First World War. Who knows what he may have otherwise produced?

Mackintosh’s four large houses are highlighted. In these, his architectural progression is the reverse of other progressive designers, running from the almost abstract Windyhill to the highly expressive Hill House, to the Jacobean Auchinibert (featured drawing above) and finally to the vernacular Mossyde. You can see him absorbing ideas from the English Arts & Crafts movement, initially at Auchinibert, partly through the preference of the client. Mackintosh’s final house, Mossyde, shows him fully resolved as a vernacular Arts & Crafts designer – an astonishing change from Hill House of only a few years earlier. Mackintosh was an architect who could develop and embrace new ideas. It is a shame that architectural work dried up after 1910 then stopping completely in the First World War. Who knows what he may have otherwise produced?

The stripping away of the myths allows Mackintosh’s true genius to come to the fore – that of a professional architect and designer of the highest calibre who buildings inspired many of his own generation and many more in subsequent generations.